It’s hard to believe it’s been over ten years since I defended my Master’s thesis. Finally, the topic is getting the attention it deserves. Germany implemented its new Accessibility Strengthening Act (BFSG) on 28 June 2025. This act brings the European directive on accessibility into effect. To celebrate this, I’m republishing an article rooted in my thesis. In it, I argued for more inclusive and accessible forms of communication.

In this work I proposed a video-telephony interface concept, developed in collaboration with the Social Cognitive Systems research group at Bielefeld University (M.Sc. Thesis, 2014). Rather than seeing it as a purely abstract method, I saw it as a tangible suggestion for designing video calls more accessibly and empathetically for all users.

In the article below, I’ll walk through how I used a user-centred design approach. This approach helped to shape the interface and its assistive features. I’ll show you how, step by step:

1. Defining context & user requirements: especially for people with cognitive impairments

2. Ideation & prototyping: iterating toward a “circle of friends” metaphor

3. Evaluation & refinement: usability testing versus conventional systems (like Skype)

In the article about Inclusive Design, I introduced you to a method for analysing the requirements of user groups with special needs.

Since the use of common video telephony systems (e.g. Skype) often poses great challenges for people with cognitive impairments, this area is particularly suitable as an area for the development and research of new methods for universal design. With this in mind, a concept for a video telephony interface was developed in cooperation between the Social Cognitive Systems working group (Cluster of Excellence CITEC and Technical Faculty of Bielefeld University) and the PIKSL laboratory in Düsseldorf. In terms of a universal design, this should be particularly easy and intuitive to use, and thus also (but not only) suitable for people with cognitive impairments.

Step 1: Describe the context of use & define the requirements for use?

For users with special needs, a mixed-methods approach has proven to be effective in determining the context of use and the requirements for use, in which several methods and sources are used to collect data.

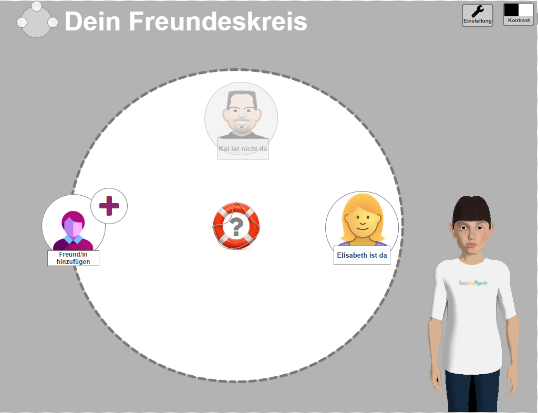

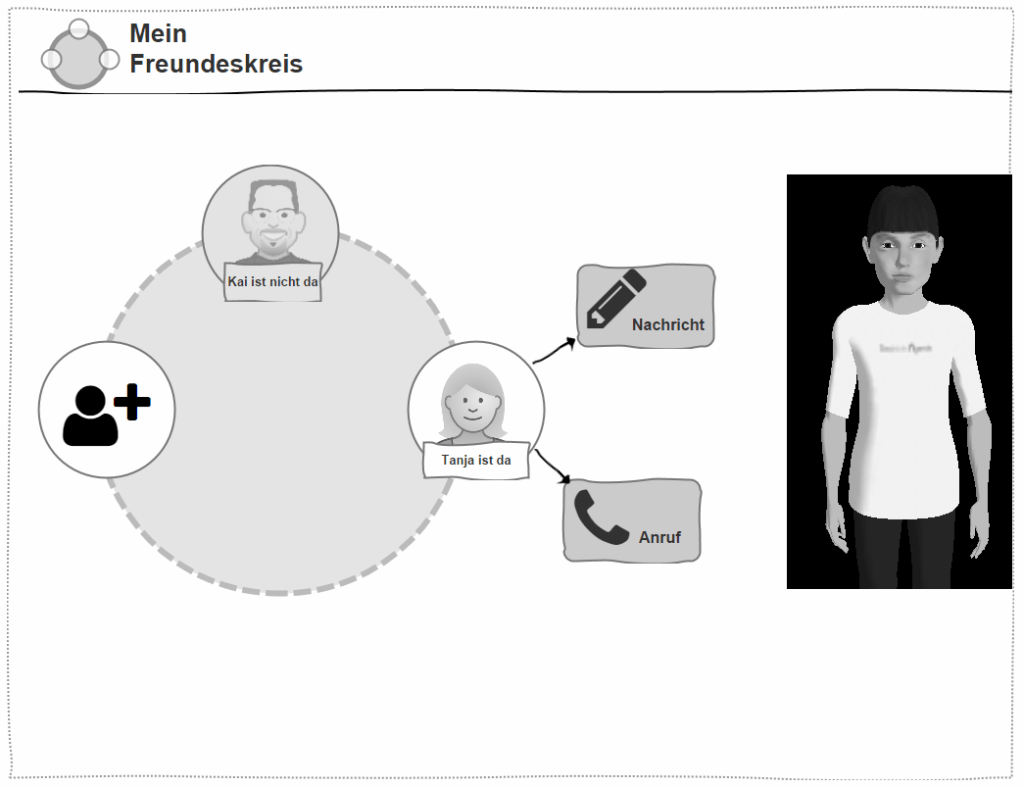

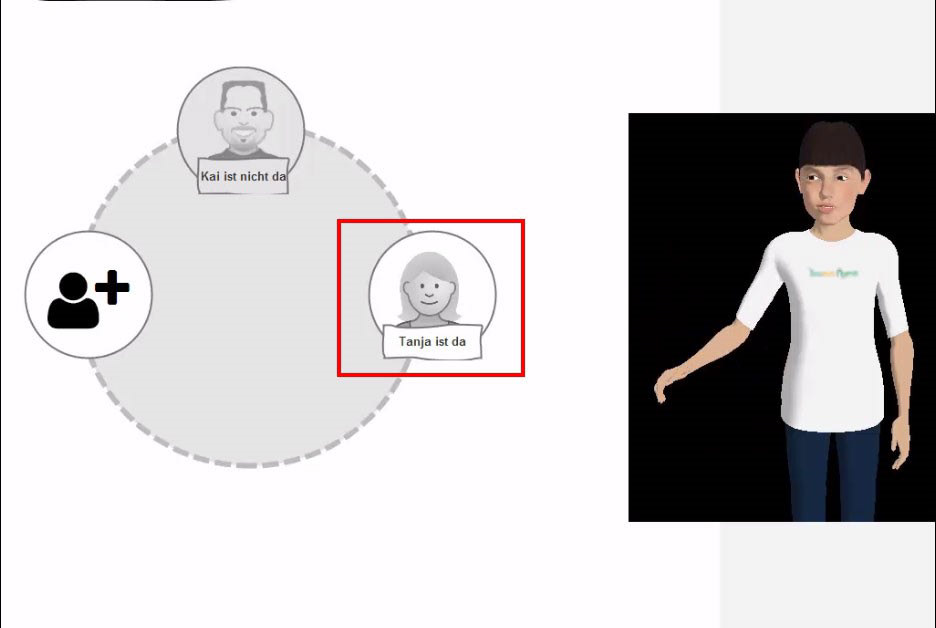

On the right you can see a screenshot of the high-fidelity prototype, which shows the “circle of friends” as a central element of the newly developed interface, and the assistance system in the form of a virtual agent. In this article the concept of “circle of friends” will be introduced further.

Focus groups as one way of gathering context of use & capabilities of users

First, the ideas and needs of the target group were identified in a focus group. The focus group made it possible to gain an insight into the users’ world of thought and problems in dealing with communication technology. On the other hand, the relaxed atmosphere also provided the opportunity for shy test persons to express themselves and report on their problems.

Ideas were also collected on the topic of “video chat”. Interactive methods are helpful here. For example, the “Draw Your Experience” approach was used, which allows participants to visualise their experiences and ideas in simple sketches with pen and paper (Dix, 2007). This approach made it possible to conceive a metaphor (here the metaphor of the “circle of friends”) for a first draft based on the users’ existing ideas.

Usability test with Skype and analysis of cognitive limitations

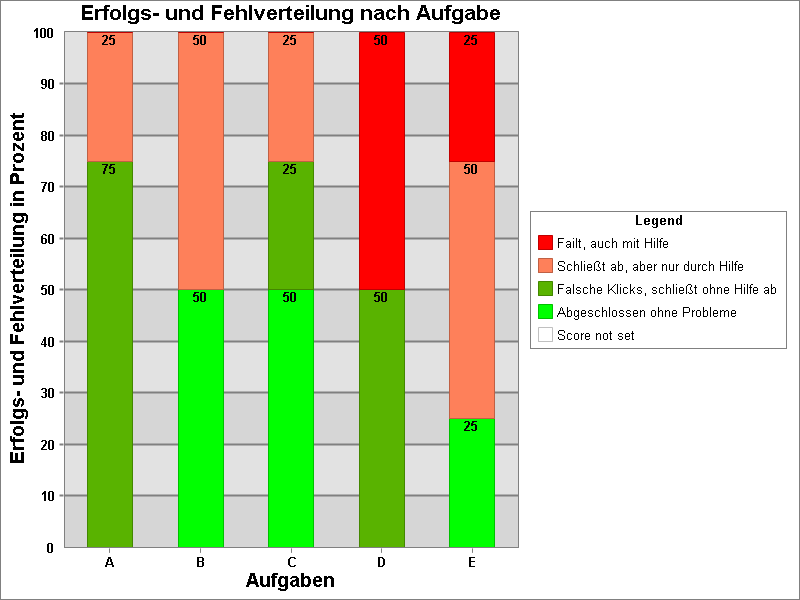

Additionally, the use of the video telephony interface Skype was evaluated in 2014 in a usability test with Thinking Aloud. The participants performed five prototypical tasks with the Skype user interface. These tasks were [A] log in, [B] compose messages, [C] make video calls, [D] adjust volume, and [E] add user. Various usability metrics were collected. These metrics included time on task, click rate, completion rate, errors, system usability scale, and single ease question. The test included a pre-test analyzing users’ cognitive limitations using Langdon’s Abilities Limitations Matrix (see Part 1) and a main test & debriefing.

The results of the pretest showed that the users had a variety of cognitive impairments, which manifested themselves, for example, in the form of difficulties with reading and writing. It also became clear that these impairments led to a high need for assistance in everyday life. The results of the pretest were included in the capabilities-limitation matrix by Jokisuu et al. that I showed in the previous article: Designing Inclusive Interfaces: A Guide for Accessibility.

Most participants told me that they do not consider themselves to be very tech-savvy. Therefore, they usually immediately ask for help when they face a problem. However, the majority of users who participated in this study were accustomed to using Skype, as they said they used this platform to keep in touch with friends on a regular basis. Based on their previous experiences, they described Skype as difficult to use. They also missed the transparency and clarity in the use of it.

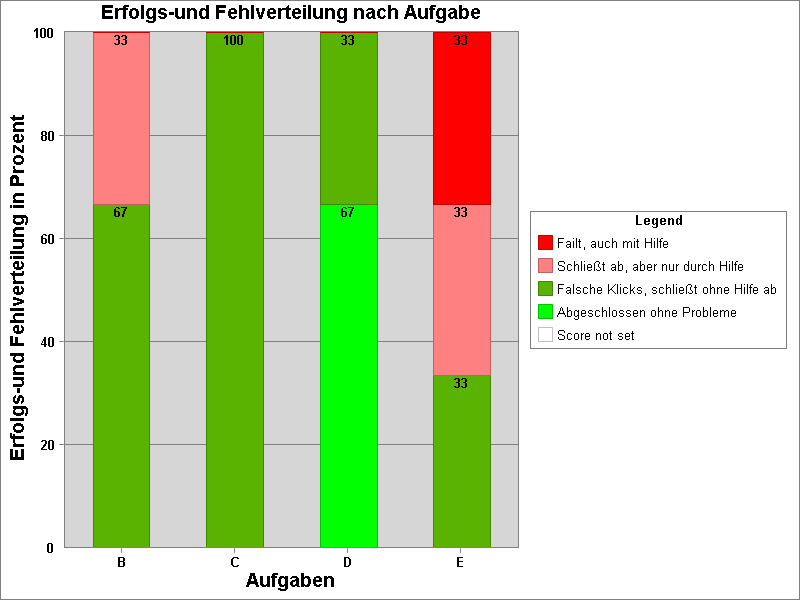

The results of the main test confirmed the problems that were described in the preceding focus group session. All Users had difficulties by completing the tasks on their own. Especially completing basic tasks, like changing the volume, adding a contact, was particularly challenging. The interface mainly failed to support the participants by demanding the users to complete the tasks in a – for the users – complex way. The figure on the right shows that the completion rate of the users is in a critical range. If at least 70% of the participants are able to complete a task without help, this can normally be considered a success. However, this was not the case for the tasks [B] compose messages, [D] adjust volume and [E] add user.

Based on these results, user requirements were defined, which built the basis for the new concept of the so called “circle of friendship” / “Freundeskreis”.

Step 2: Ideation and conception of the new interface with an assistive system

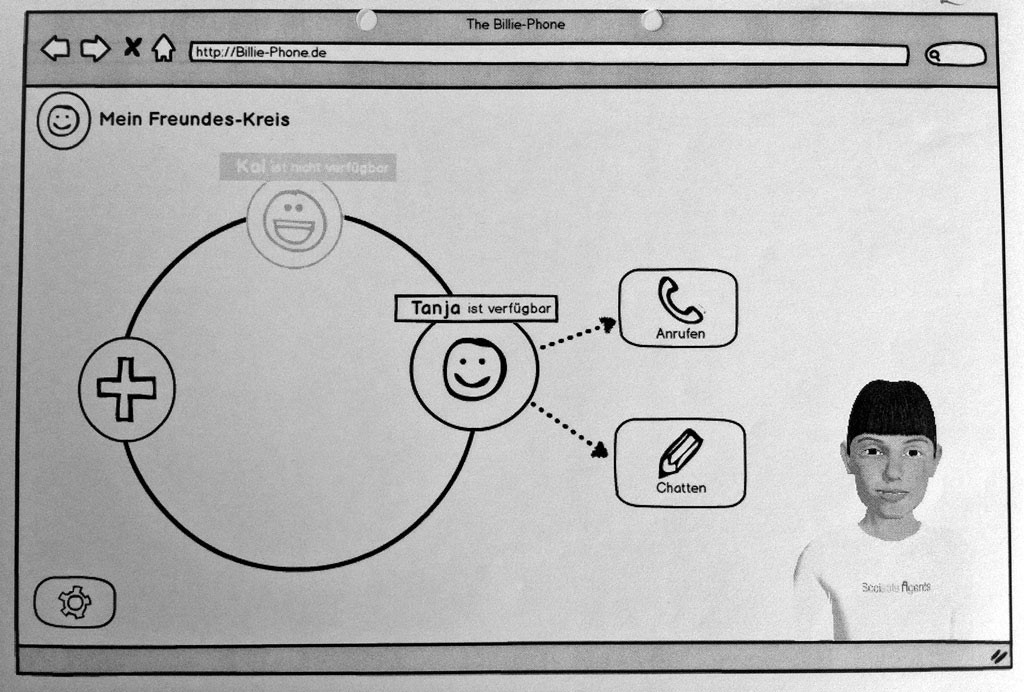

First, a static low-fidelity prototype was created which then was iterated to a high-fidelity prototype. The pictures on the right show the progress of different visualisations of the user interface that resulted in a higher fidelity with each iteration. Key usability principles (Norman, 2014)and guidelines for accessibility (BKB, 2011) were combined with principles of Universal Design. For special support an assistance concept was included that consisted of a virtual, conversational agent for offering contextual help. This agent supported the participants on demand with multimodal explantation and help which were specifically targeted to build up the participant’s mental model of the application.

This has the advantage that users with cognitive disabilities, together with the virtual agent, better understand how to solve problems when using the application. It also helped them to explore the user interface without fear of making a mistake. To give the users the control about the amount of help, they were offered to activate or deactivate the assistant on demand.

The 1st picture in the gallery on the top shows the static paper prototype, visualising the metaphor of “Circle of Friends”. The 2nd picture in the gallery on the top shows the interactive interactive prototype with visible interaction buttons “writing a message” and “make a call”. The 3rd picture shows an assistance situation: Embodied Conversational Agent ‘Billie’ explains the interface “Circle of Friends”. Objects are highlighted during the explanation.

Step 3: Usability test with new developed prototype

The interactive prototype was eventually evaluated in a usability test with three users of the main target group. This setting was methodologically identical with the previous test setup of the Skype evaluation, to be able to compare the results afterwards.

The usability problems uncovered and the recommendations derived from by the participants were finally incorporated into an updated iteration of the existing prototype.

The results of the evaluation study have shown a positive impact of the concept design compared to the use of Skype. For example, the percentage of tasks completed successfully and without assistance increased from 50% to 67% for writing a message, from 75% to 100% for calling a contact, from 50% to 100% for adjusting the volume, and from 25% to 33% for adding a friend. However, a comparison between the usage concepts of Skype and Circle of Friends cannot be based on quantitative data alone, as the interfaces have different degrees of fidelity. Nevertheless, it is the individual statements of the users from the think-aloud protocols that provide information about user satisfaction with the interfaces. These speak to the success of the user-centered orientation in the design of the Circle of Friends video telephony interface.

Conclusion

The design of accessible interfaces is, in any case, a worthwhile endeavor. Accessible interfaces will increasingly become our concern in the future, and with them, the inclusion of users with special needs. We need practical methods to provide solutions to the problems of the future. In the articles on inclusive systems and inclusive design, I wanted to contribute to the ergonomic design of user interfaces in the field of video telephony. On the other hand, it was my intention to also show potential for making currently widespread systems such as Skype easier to use. Furthermore, the integration of a virtual agent to assist users provides a use case for combining an embodied conversational agent with elements of graphical user interfaces to synergize the advantages of these two different forms of interaction. Finally, it also makes a methodological contribution to the user-centered design of human-machine interfaces. It shows that the input of cognitively impaired people in the development process not only provides valuable contributions to technology design, but it also contributes to a sense of universal design for making interface interaction more accessible for all.

References

This article is part of the paper: “Universal Design for and with people with cognitive disabilities” (Pagel & Bergmann, 2016), which was presented during the 5th Interdisciplinary Workshop “Cognitive Systems: Humans, Teams, Systems and Automata”, on 14 – 16 March 2016 in Bochum. It was also published on http://www.usabilityblog.de in 2017.

- Bundeskompetenzzentrum Barrierefreiheit e. V. (BKB) (2011) Barrierefreiheit für Menschen mit kognitiven Einschränkungen: Kriterienkatalog: BKB.

- Dix A (2007) Human computer interaction. Harlow, England [u.a.]: Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Norman DA (2014) Some Observations on Mental Models. In: Gentner D and Stevens AL (eds) Mental Models. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis, pp. 7–14.

- Jokisuu E, Langdon PM and Clarkson PJ (2012). A Framework for Studying Cognitive Impairment to Inform Inclusive Design. In: Langdon P, Clarkson J, Robinson P, Lazar J and Heylighen A (eds) Designing Inclusive Systems: Designing Inclusion for Real-world Applications. London: Springer London, SS. 115–124.

- Pagel P & Bergmann K (2016). Eine Videotelefonie-Schnittstelle mit Assistenzsystem für Menschen mit kognitiven Einschränkungen. In: Eyssel F, Kluge A, Kopp S, et al. (Eds.), Proceedings 5. Interdisziplinärer Workshop Kognitive Systeme: Mensch, Teams, Systeme und Automaten.