Human Centered Design — making things easy to use: Technology should adapt to the way humans are, not the other way around.

When designing an interactive system with ‘accessibility’ as a key user need, the challenge is clear. We need to create an interface that is easy to use for people with special needs. At the same time, it must be user-friendly for everyone else. The solution must meet usability criteria, ensuring it remains cost-effective and time-efficient.

Advantages

The user-centered design approach according to DIN EN ISO 9241-210:2011 (UCD) provides a good basis. The advantages of the process are clear:

Simplification of the operating concept and associated visualisation of the information architecture/interface etc.

+ Fewer support requests due to improved usability.

+ Positive image to the outside world.

+ Proven better user experience for all users.

+ And last but not least: legal certainty for the future.

The user-centered design approach is also called inclusive design. It is known as universal design or design for all. This is particularly important in the context of developing interfaces for people with disabilities. I mainly refer to Universal Design. Optimally, an interface fulfills its seven principles:

Principles that deal primarily with people

- Principle 3: Simple and intuitive use

- Principle 4: Sensory perceptible information

- Principle 6: Low physical effort

Principles that relate primarily to the process

- Principle 2: Flexibility in use

- Principle 5: Fault tolerance

- Principle 7: Size and space for access and use

Principles that transcend people and process

- Principle 1: Broad usability

Challenge: Analysing requirements

The correct understanding of the context of use is essential for the success of inclusive design. The UCD process requires defining user requirements accurately. Designers and developers need appropriate methods to design interfaces for people with disabilities. There is a lack of literature on people with cognitive impairments regarding the practical development of interfaces. As a result, there is hardly any data material or best practice studies on this. Unfortunately, accessibility experts are often involved too late in the development of barrier-free interfaces. System decisions are often made in advance. Universal design can’t be successfully implemented on every platform. A rule of thumb says that accessibility becomes expensive and insufficient if it is to be “tested into” a product after the release. However, accessibility stays cost-neutral when the requirements of people with disabilities are taken into account from the start. (UPA Accessibility Working Group, 2007).

What are cognitive impairments or cognitive limitations?

It is first important to clarify what is meant by the term “cognitive impairment”. Cognition refers to the information-processing capabilities of the brain. This includes the basic abilities such as perception and attention. It also encompasses the executive abilities such as planning, problem-solving behaviour, and the ability to reflect. Other abilities include the capacity to formulate language and calculate, etc. (Schutz and Wanlass 2009). These abilities enable us to consciously perceive our environment and act intelligently.

If parts of these abilities are restricted or lost, one speaks of cognitive impairment(s). However, the phenomenon itself cannot be captured in a definition. In the literature, there is no uniform definition of the cause of cognitive impairment. The reason for this is that appearance and manifestation depend on individual physical factors. They also rely on social factors. These factors are as individual as the people they affect. For the design of barrier-free interfaces, this means a change in requirements. It is thus advisable to consider users with cognitive impairments in varying degrees of severity in the development process.

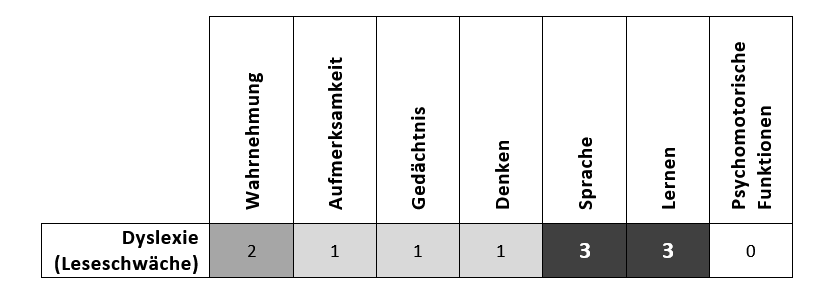

For this reason, I propose an extended user-centered approach that takes into account the principles of universal design. This uses the so-called Abilities-Limitations Matrix by E. Jokisuu et al. (2012). This is used to systematically elicit the requirements of users with cognitive impairments for an inclusive design. An example matrix is shown in Table 1. In it, causes of cognitive impairments are placed in a weighted relation to cognitive functions. The matrix form is a clear way to represent information. Designers can easily understand and use it in the conception process. From this, designers can directly derive the implications for the conception. This was not possible before with the usual methods and this target group. If people have a reading disability, for example, it impacts language. It also affects learning ability. For designers, this does not only mean using simple language. They have to visualise as much as possible for the users. Symbol-text combinations are a good choice for buttons. Multimodal output through speech facilitates comprehension. Tutorial functions are particularly useful in the area of learning.

Understanding constraints on the UCD process

Back to the matrix: To create this, map the medical condition or impairment patterns as causes in the rows. Map the cognitive abilities in the columns. Then, rate the strength of the link between each medical condition and the cognitive ability it typically affects. Use a scale of 1 to 3. 1 indicates a weak link, while 3 represents the greatest influence of the cause on cognitive function. 0 indicates that there is no known link between the clinical picture and cognitive function. Designers can thus quickly identify which aspects they need to pay particular attention to in the design. The data used here comes from contextual interviews with users evaluating a video telephony application. With the help of the tables linked here, the individual dimensions are defined from the columns of the matrix.

Reminder: Ideally, the data needed for the matrix should be collected for each target group. This is important because the characteristics of individual limitations may change.

With enough data, a pattern can emerge. Assessing the individual connections simplifies the identification of the problem areas of the user group. A prerequisite for this approach is to gather data on individual users’ medical history. This should be done during the requirements analysis, e.g. in contextual interviews. Quick tests like the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) test can complement this. The MoCA test was developed to identify cognitive impairments and assess their severity. The framework itself is still in an early stage of development, so there is potential for optimisation. At the same time, it offers a decisive approach to involving people with cognitive impairments in the development of user interfaces.

This article is part of the paper: “Universal Design for and with people with cognitive disabilities” (Pagel & Bergmann, 2016), which was presented during the 5th Interdisciplinary Workshop “Cognitive Systems: Humans, Teams, Systems and Automata”, on 14 – 16 March 2016 in Bochum.

References

- Jokisuu E, Langdon PM and Clarkson PJ (2012). A Framework for Studying Cognitive Impairment to Inform Inclusive Design. In: Langdon P, Clarkson J, Robinson P, Lazar J and Heylighen A (eds) Designing Inclusive Systems: Designing Inclusion for Real-world Applications. London: Springer London, SS. 115–124.

- Pagel P & Bergmann K (2016). Eine Videotelefonie-Schnittstelle mit Assistenzsystem für Menschen mit kognitiven Einschränkungen. In: Eyssel F, Kluge A, Kopp S, et al. (Eds.), Proceedings 5. Interdisziplinärer Workshop Kognitive Systeme: Mensch, Teams, Systeme und Automaten.

- Schutz LE and Wanlass RL (2009) Interdisciplinary assessment strategies for capturing the elusive executive. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation / Association of Academic Physiatrists 88(5): 419–422.

- UPA-Arbeitskreis Barrierefreiheit (2007): „Barrierefreiheit – Universelles Design“.

This article was originally published on http://www.usabilityblog.de.

One response to “Designing Inclusive Interfaces: A Guide for Accessibility”

[…] This article adds on the topic of Inclusive Design. […]