Human Centered Design — making things easy to use: Technology should adapt to the way humans are, not the other way around.

Cognitive Crash Dummies ( Photo by Alexander Schimmeck on Unsplash )

The field of Human Computer Interaction (HCI) has always been concerned with, among other things, the question of how human behaviour can be analysed and predicted.

In the age of digitalisation, the following question is becoming increasingly immanent: In the stressful everyday life of a design project, wouldn’t it be nice to have a method at hand that makes it easy to assess the efficiency of use cases and their UI variants even without the use of real users? In this article, I introduce you to model-based evaluation with a focus on GOMS (Goals, Operators, Methods and Selection Rules, Card et al. 1983). By applying GOMS it is possible to have the efficiency of interfaces evaluated by virtual test persons, also called cognitive crash dummies.

The scenario

Imagine the following completely realistic situation: You have created several variants of use cases for a new insurance application section to be developed, which will differ in their UI. Before you go into the design phase, you would like to identify time-consuming use cases and validly estimate how long it will take users to reach their goal. However, your prototype is currently so rudimentary (or non-existent) that it is not suitable for a usability test. In addition, the project resources are very scarce anyway, so that a test of the interface would only be possible with a few users, which would further minimise the significance of the task time collected. You don’t want to and can’t wait for an A/B test either (too little developer time or even too little traffic to measure significance).

It would be ideal to be able to decide with which design the user reaches his goal faster with little effort. In this way, you could determine which design does not work at all and establish tangible figures about how much progress you are making compared to a competitor’s design.

When we conduct or accompany a conceptual design project, optimising efficiency or saving time is an essential characteristic of good usability. The gold standard in HCI is to conduct an empirical evaluation with an appropriate number of users, where we record various metrics of usability and satisfaction.

In order to make statements about effectiveness, a heuristic evaluation (expert review, cognitive walkthrough) is also possible, in which the evaluation is made on the basis of recognised heuristic methods and domain or expert knowledge. However, data on efficiency cannot be collected in this case.

The solution to the puzzle: Formal evaluation and Cognitive Crash Dummies

For the scenario outlined at the beginning, formal evaluation methods for measuring efficiency come into consideration. So-called ‘Human Behaviour Models’ or ‘Cognitive Crash Dummies’ (B. John 2014) are used, i.e. mathematical models with the help of which the behaviour of people can be simulated. These can be used to make assumptions about how easy and efficient interfaces are to use.

Unfortunately, these models are quite neglected and often dismissed as too scientific. Yet they can fill the gap between empirical and heuristic evaluation quite well. So why “too scientific”? Indeed, since the 1980s, cognitive architectures have been developed that can be used to make assumptions about human thought and action processes (e.g. SOAR, ACT-R). These are used, among other things, in virtual agents (Billie, Alexa, Cortana, Watson, etc.) to enable natural decision-making patterns. A major problem with this was and still is the lack of accessibility for everyday project work, which is made more difficult by aspects such as difficult calculations, elaborate creation of workflows. In short, the reason why formal evaluation is so little used is that it is perceived by UX designers and developers as too difficult and cumbersome to learn. However, they offer some advantages for the optimisation of user procedures, which could usefully complement the empirical or heuristic approach: “Using KLM you can predict a skilled user’s task time (error-free) to within 10-20% of the actual time. To put this amount of error in perspective, it would take testing 80 users to have the same margin of error as using KLM.” (Sauro 2009)

GOMS model

The basic model for formal evaluation is GOMS (Goals, Operators, Methods and Selection Rules) and describes a family of several modelling techniques. The basis is to reduce user behaviour to the elementary actions. These actions are then represented in a model to determine the efficiency of the actions.

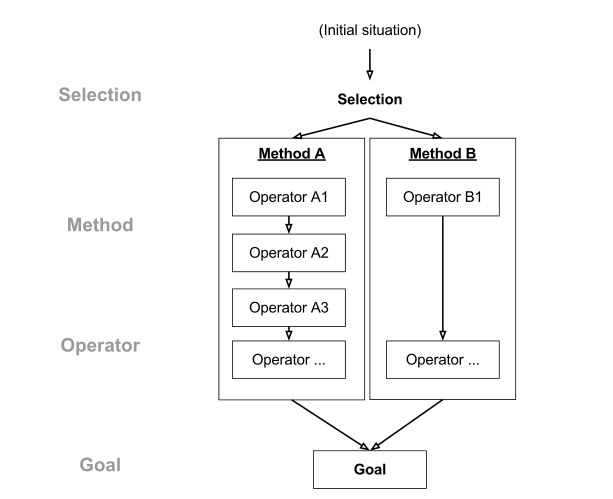

A GOMS model therefore consists of methods that are used to achieve goals. A method consists of a sequence of operators (sequences of actions) that the user executes, which also include intermediate goals. If there is more than one method that can be used to achieve a goal, a selection rule is applied to determine the appropriate method depending on the context. The following figure shows the process.

Image on the right: Visualisation of the CMN-GOMS model to analyse the efficiency of a task sequence in the CMN-GOMS method (Wikipedia Commons licence.

Since their development in 1983, the model family has been steadily expanded. Some variants are:

⦁ The original Card, Moran and Newell-GOMS method (CMN-GOMS)

⦁ The simple Keystroke Level Model (KLM-GOMS) which takes into account the interaction on the computer with mouse and keyboard

⦁ Natural GOMS Language (NGOMSL) with which assumptions can be made about the learning activity

⦁ Cognitive-Perceptual-Motor-GOMS (CPM-GOMS) is the most complex variant enables the representation of parallel asynchronous thought and action processes (multitasking); assumes that cognitive processes take place in specialised processors (visual processor, motor processor etc.)

⦁ Touch Level Model (TLM) – Extension of KLM to cover the operating sequences via a touch interface of mobile terminals.

There are many areas of application for GOMS. Some of them are listed below:

⦁ Can be used in all phases of conception and system development (new design, redesign, evaluation, maintenance)

⦁ Assumptions about efficiency of a future design before implementation starts

⦁ Enables comparisons of the efficiency of different design variants without finished prototypes

⦁ Cost-saving, as no real test persons are necessary

⦁ Enables visualisation of the entire procedural knowledge and thus makes it possible to better understand the thought processes of users when working on tasks

Apply Keystroke Level Model

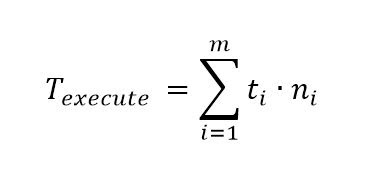

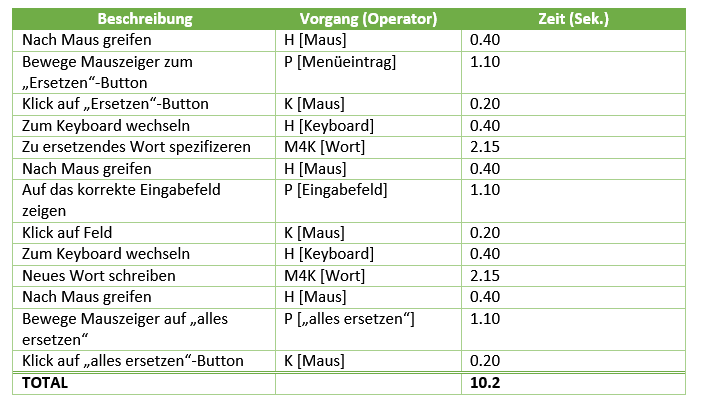

I briefly describe which steps are necessary to carry out a KLM-GOMS analysis. KLM does not use objectives, methods or selection rules like CPM-GOMS, but due to its low complexity it is well suited to get an understanding of GOMS. It can be summarised in the simple formula that is shown in the picture.

Image on the right: Calculation of the execution time in KLM-GOMS. Texecute = execution time; t= execution time of an operation; n=frequency of the single operation; i = run index

To perform a KLM-GOMS analysis of an interface, the following steps are necessary:

1. One or more representative scenarios are selected.

2. Design is specified to the extent that it is possible to list the keystroke level actions.

3. List the keystroke level operators that are applied in the task.

4. Adding Mental Operators (M) at specific points (M operators are placed at the points where experienced users are assumed to pause or perform search actions and thought processes, based on empirically-validated heuristics).

5. An empirical-verified implementation time is added to each operator.

6. The output is the time a user needs to perform a task with the corresponding system.

Some operators with execution times necessary for analysis are listed below (taken from Kieras 2001):

⦁ K (keystroke) – 0.8 to 1.2 sec

⦁ K (mouse) – 0.1 – 0.4 sec

⦁ P (point with mouse) – 1,10 Sec

⦁ H (home hands between devices) – 0.40 sec

⦁ R (system response time) – Depending on the system

⦁ M (mental operator) – 0.6 to 1.35; average 1.2 sec.

Would you like to try it out for yourself? In an article on KLM, Jeff Sauro has built a small tool with which KLM can be tested using the example of a comparison between drop-down and radio button selection. MIT also offers a simple calculator that can be used to quickly determine the execution time.

Tools for practical use

Since the calculation of GOMS models can be quite time-consuming, several tools have been developed in the past which partially combine the GOMS variants described above. They make it possible, for example, to also perform CPM-GOMS analyses with little effort.

CogTool

CogTool is an open source application by B. E. John (Carneige Mellon University) from the field of lean methods that combines various GOMS variants and a rudimentary prototyping tool. One should not be put off by the somewhat old-fashioned appearance of the programme. The calculations of the CogTool are based on the cognitive architecture ACT-R and Fitt’s Law. The Cog-Explorer can also be used to track the virtual course of gaze. This allows paper and pencil prototypes to be formally evaluated and potential for optimisation to be identified.

The following pictures: 2 steps to create a GOMS model & visualise the operating sequences with CogTool taken from B. E. John 2014).

The app can be obtained free of charge from the project page.

How To tutorials and webinars were made available on Youtube to learn how to use CogTool.

Furthermore, it creates a visualisation of the action and thought processes, which is particularly beneficial when comparing different designs or use case versions.

Cogulator

Restrictions on the use of GOMS

For all the joy of agile methods and lean management in the use of GOMS, there are limitations. GOMS models human operating procedures quite strictly to specific tasks. Therefore, it is well suited for usability analysis of different interfaces with redundant task flows, such as in help systems, training systems, etc. However, Olson and Olson already pointed out in 1990 that GOMS does not take into account important aspects of HCI such as individual user acceptance, fatigue, inter-user skills. The analysis always assumes an experienced user who does not produce errors. Although this is useful for the pure comparison of interfaces and for the rigorous analysis of efficiency, it cannot be completely projected onto realistic human application scenarios. A detailed list of the limitations of GOMS can be found in Card et al. (1980).

The inclusion of real users is indispensable in user-centred design when the abilities, needs and expectations of the users are taken seriously. GOMS can be a good addition for optimising application processes or comparing interface variants in terms of efficiency. The heuristic evaluation, on the other hand, offers the possibility of a more cost-effective evaluation of effectiveness based on expert knowledge. However, only an empirical evaluation will provide you with data on how users with different abilities use an interface. Finally, a usability test also gives you the best feedback on the joy of use and thus the user experience.

References

Links and recommended reading

If you would like to delve deeper into the topic of formal evaluation, you will find a non exhaustive mix of links to primary and secondary sources below.

- J. Raskin (2000): The Humane Interface: New Directions for Designin Interactive Systems

- User Experience Professionals’ Association (2012): KLM-GOMS.

- Sauro, J. (2011): Measuring Task Times without Users.

- Card et al. (1980): The Keystroke-Level Model for User Performance Time with Interactive Systems.

- Rice, Andrew D. and Lartigue, Jonathan W. (2014) Touch-Level Model (TLM): Evolving KLM-GOMS for Touchscreen and Mobile Devices

- John, Bonnie E. and Kieras, David E. (1996): The GOMS family of user interface analysis techniques: comparison and contrast. In ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, Volume 3 , Issue 4, pages: 320 – 351.

- R. Olson, G. Olson (1990): The Growth of Cognitive Modeling in Human-Computer Interaction Since GOMS

- Kieras D. (2001): Using the Keystroke-Level Model to Estimate Execution Time

This article was originally published on http://www.usabilityblog.de.